A Black-and-White World

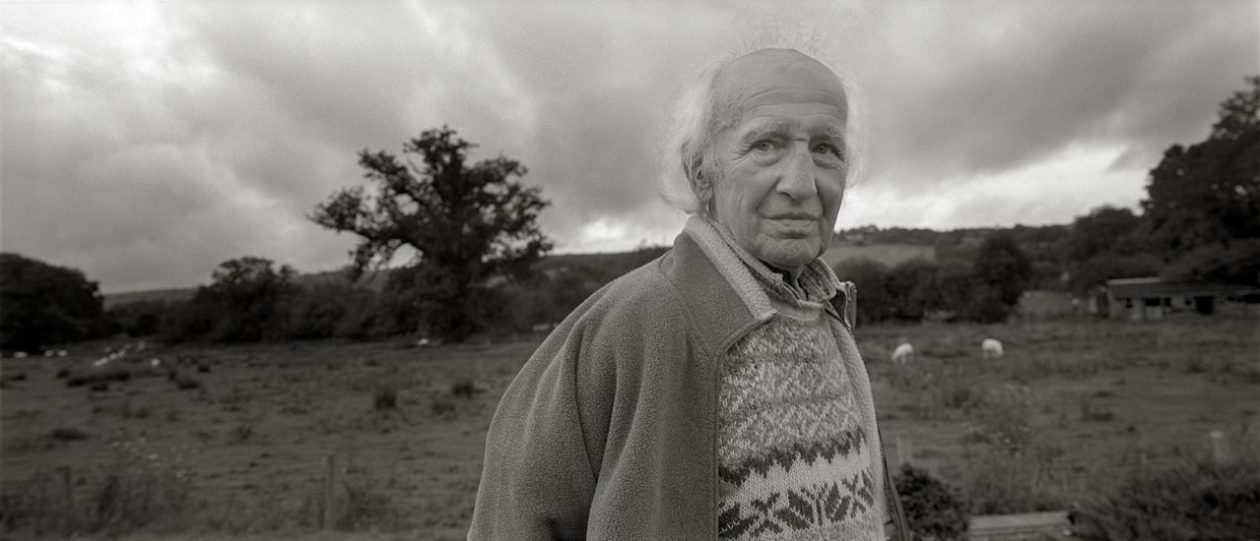

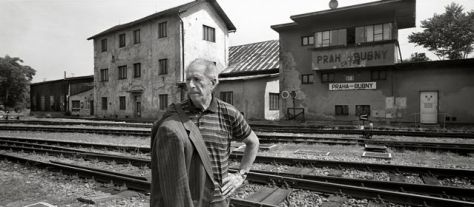

Presented as a series of encounters between its subjects and photographer Dennis Darling, the film will alternate between color and black and white. Its black-and-white content ties into Darling’s own use of black-and-white still photography to create his portraits, as well as the survivors own pre-war black-and-white photographs. Each encounter will end with a lingering image of Darling’s final portrait, giving the story a final visual statement and a sense of closure.

The Miracle of Survival

As he photographs his subjects, Darling asks what they think allowed them to survive when most others perished, including members of their own family. Their answers range from good luck to hard work, from serendipity to special skills. In the end, though, they view their survival as miraculous. And as they answer the photographer’s questions, the subjects tell stories about their wartime experience and survival that, in some cases, they have never shared with anyone before. In this way, the film’s viewer is taken into confidence that sheds new light on the Holocaust.

A Sense of Place

Though the film’s subjects are often first encountered in their own homes, the photographer takes them to places that relate to their stories of survival-some of these in the U.S. and some in the Czech Republic, depending on where they now live. He photographs them in those environments, some of which they haven’t seen since the end of World War II. The film documents their response to these places and the stories evoked by them, a process aided by the use of pre-war family snapshots from the subjects’ own collections. (These images will be shown full-frame onscreen.) In some cases, the old photographs actually show the place being visited, whether at Terezin itself or in the subjects’ former Czech neighborhoods.

The Passage of Time

In pairing old snapshots with the new portraits being created by the photographer, the time evokes a powerful sense of the passage of nearly 70 years since the end of the Holocaust. But rather than make those terrible events seem historically distant, the film brings them to the fore by engaging its subjects in a conversation about experiences that are often still fresh and profoundly traumatic to them. And showing survivors as they move through these environments and react to them, the film avoids the static, interview-style approach that can make historical documentaries seem dull to a younger audience that expects active camerawork. In this way, the film will fulfill its task of reaching younger viewers who need to know about the horrific events of the Holocaust.

Through the Generations

In order to interest a younger audience in a subject as dark as the Holocaust, the film will also show the survivors’ descendants-children and grandchildren. Sometimes these people know their parents’ or grandparents’ stories of survival, and can even help fill them in for failing memories. In other cases, though, the story is either ancient, forgotten history-or has never been told at all. The film’s viewer will identify with these second-and third-generation family members as they interact with the survivors and revisit the formative struggle of these once-shattered lives. The hope is to educate a younger audience about a history that must never be forgotten.

Humor in the Darkness

Humor is a powerful tool for psychological survival, as most of us know. And the film’s survivors often find humor in their own immensely difficult past, as well as in the circumstances of being the subject of a film on the Holocaust. In the interaction between the photographer and the subject, there are often funny moments that not only lighten the tragic aspect of the film but add to the viewers’ understanding of how these people were able to overcome such an awful experience. The survivors’ ability to laugh has, in many cases, made it easier for them to defy death-and is yet another way in which the film engages an audience that might otherwise turn away.

The Narrative Voice

The viewers’ “guide” and the provider of some of the film’s voice-over, is the photographer himself. Professor Dennis Darling, who teaches photography at the University of Texas, has been working on his portraits of Holocaust survivors for five years. As Darling explains in the film, part of his inspiration to pursue this project was his own father’s role in World War II, as the pilot navigator of an American B-52 that flew bombing missions over Germany. The film details the research that Darling undertook to locate the last living survivors of Terezin, and how he arranged the encounters that led to his remarkable photographic portraits. Other narration in the film will be provided by professional actors, including celebrities who are interested in the preservation of this important history.

Families Gone to Ash

There are fewer than 1,000 survivors of Terezin alive today out of the original 20,000 that survived the concentration camp. Most of them are in their late eighties and early nineties, with a few as old as 100 years more. The oldest known survivor, who Dennis Darling photographed in 2012, recently died at the age of 110. Every year from 30 to 50 of these people die. This gives Darling’s photographic project a special urgency as he travels around the world to capture these survivors’ stories and portraits. Titled Families Gone to Ash, the project now consists of approximately 60 portraits, and Darling plans to continue his important work for as long as time allows.